MANHATTAN TRANSFER: TEXT ANALYSIS WITH VOYANT

A distant reading of Manhattan Transfer through Voyant Tools

Laura Travaglini

Abstract: Voyant Tools is a quite popular open-source, user-friendly, online-based platform for the analysis of digitally recorded texts. We made use of it in order to investigate a long-forgotten classic of the Jazz Age, "Manhattan Transfer" by John Dos Pass, - a dense, complex, pioneering book inhabited by plenty of characters immersed in the lively New York City of those exciting times - and see which type of information would have come out, which results and which flaws.

1. Introduction

The tool: Voyant

Voyant Tools is an open-source, user-friendly, online-based platform for the analysis of digitally recorded texts developed by Stefan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell. Using computational algorithms, the platform is able to extract linguistic and statistical information from texts of different sizes, types, and languages within seconds. All extractions are available in visual formats to offer a window for a macroscopic view of texts. This input-output process allows for turning complex metadata into easily interpretable visuals.

The text: Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos (1925)

Manhattan Transfer is, unfairly, a long-forgotten classic of the Jazz Era. Generally clouded by the more famous contemporary Fitzgerald, Dos Passos has nothing to envy his peer: in this 1925’s gem, he was able to depict the changes of a generation of writers, being pioneering and experimental with his own style, and the changes of the Big Apple, the object of fascination for him and his colleagues.

Manhattan Transfer was for New York what Waste Land - the masterpiece by T.S. Elliot - was for London: he painted an archetypal, variegated and visionary city, where anything can and actually happens, where immigrants coexist with the king of millionaires, where scams and adulterers, of shops and loves, and broken dreams are commonplaces.

What’s really captivating lies in his unique style, in the fragmented construction, which is never recomposed, not at all consoling, not at all "choral". Despite being inhabited by several characters, from different extractions and nationalities (Germans with the Kaiser in mind; Italians who have known Malatesta and dream of anarchy; French who have landed in Manhattan after having travelled half the world, from one colony to another; Jews not yet fleeing from Nazi persecutions) and trying to follow them in a span of more or less twenty years, Manhattan Transfer gives back the impossibility of giving the metropolis and its people a unitary, orderly, rational, intelligible vision.

As fascinating as this can be, Manhattan Transfer may have also experienced such little glory because of this. That’s why computational text analysis can walk us through such complex text, and can help us highlight some more textual aspects or, at least, give back prior knowledge before dwelling into a more specific study with other types of tools.

In fact, what Voyant allows the user to do - however little - is to have a great research starting point, thanks to the 29 analytical tools it provides. Among these, we picked those who could give us more insights on the book’s structure and inner evolution with a specific focus on its numerous characters.

2. Methodology

Data cleaning

Prior to uploading text, the first operation was to clean the text and delete those parts which were not going to matter in terms of analysis once inside Voyant: for example, the very beginning and very end of the book with titles, tables of contents, and copyright lines, markup tags and page numbers. The clean-up phase increases the accuracy of the analysis and can be done by using a text editor tool, in our case Sublime Text.

By sections and by chapters

Then, given that Voyant automatically analyses work by dividing them into ten parts, other two versions of the text were created. One time the cleaned-up starting version was divided into the three main sections of the book, the second by the eighteen chapters. Further ahead this decision will get clearer when we will go through the results.

Uploading

Voyant is compatible with a wide range of document formats, including plain text, HTML, XML, PDF, RTF, and MS Word. Our text downloaded from Wikisource was in .txt and was uploaded inside Voyant first as a single text and then as a corpus of texts in the two versions created as previously explained (one divided by sections and one by chapters).

3. Cirrus

“Cirrus is a word cloud that visualizes the top frequency words of a corpus or document.”

The world cloud provided by the Cirrus tool - by default in the top-right corner of the window - visually represents the most frequently terms, positioned and sized accordingly to the value of their frequency.

Among its option, the default stop-words list was improved with a more complete one integrated with misspelt terms or incorrect spelling often put by Dos Passos to recreate spoken language, dialect or accent (see the tag < orig > in Text Encoding part).

Here you can dowload the list.

Analysing the results immediate assertations can be done.

Dialogues

The word “said” seems to appear almost four hundreds times and if we take into account also the other most frequent terms semantically related to it - such as think (189), say (154), voice (135), talk (88) and says (56) - it is clear that dialogues, thoughts, direct and indirect speeches are a massive part of the text.

And this, despite Dos Passos’s fragmentary style and the fact that sometimes he doesn’t even introduce dialogues or mark in any way the beginning or the end of speeches.(Some talked about the use of “montage” with very rapid cuts from one character or one scene to another, creating an overall sense of disorientation. Gretchen Foster in “John Dos Passos’ Use of Film Technique in Manhattan Transfer & The 42nd Parallel” hypothesis this coming from his admiration for D. W. Griffith’s movies.)

Therefore, the high frequency of this set of terms tells a lot about it and their space in the narration.

People

Besides a couple of personal names already popping out among the most frequent terms, it is evident how “crowded” the text is.

The word “man” with its frequency of 382 times is the second most repeated, then let’s pick also eyes (237), face (234), hand (184), head (184), mr (155), feet (143), girl (140), hands (130), hair (127), people (116), young (113), woman (192), mouth (101), hat (98), men (96), mrs (81), mother (79), dress (71), arm (65), arms (63), faces (56).

Jimmy (and Ellen)

With 240 appareances, Jimmy is listed among the most frequent words. Without further information, we may assume that he must be the protagonist or at least a prominant character. Indeed he is.

Jimmy Herf in fact is the only character to be present from the beginning to the very end of the work, we see him arriving in New York as a teenage immigrant from Europe, then struggling after his mother’s death and in a troubled journey to find a job and himself, until his departure from the Big Apple which is the closing event of the book.

Note that Jimmy is just one of the many way this character is addressed in the work, see the “Trends” paragraph for a more detailed analysis.

Right after Jimmy, Ellen (153) seems to be the second most frequent character.

We first meet her at the very beginning of the book, when she is just a newborn baby (Ellen Thatcher). We then see her grow up and interect with different characters for different reasons (career or relationship motives) and watch her become Ellen Oglethorpe, then Ellen Herf, and finally Ellen Baldwin. Also, her friends and acquaintances call her by a variety of names: Ellie, Elaine, Helena, and, again, Ellen.

This subject and her evolution within the text will be better explained in the "Trends" paragraph.

Settings

Among the other most frequent words we may find verbs or nouns related to spaces or motion - go (358), see (260), going (217), door (207), room (192), went (172), street (167), walked (127), bed (107), looked (103), corner (85), avenue (75), city (71) - and time - time (168), night (112), day (81), years (72). We already mentioned Dos Passos’ cinematic style and these new elements may just confirm it.

New York can be found basically at any given moment: characters move in and out of places, cross streets, take taxis to reach restaurants or hotels, to meet other characters at night or during the day.

It’s clear that the book gives back a quite lively portrait of the Big Apple during those years and just by this quick overview we get how the vocabulary itself shows it.

4. Summary

The Summary tool - by default in the bottom-left corner of the window - is a great starting point in order to collect general information about the text we are analysing. It provides an overview of the work with a bulleted list of the following categories:

- the actual overview including the number of documents in th text or in the corpus, number of words, and number of unique words;

- the top longest documents (by the number of words) in the corpus, and the shortest documents. Following each title the actual number of words is provided in brackets;

- the documents with the top vocabulary densities, and the documents with the lowest;

- an approximation of the average number of words per sentence, both the highest and lowest values;

- the five most frequent words in the corpus, with their frequencies, indicated to their right in brackets;

- the five words with the most notable peaks in frequency;

- the top five most distinctive words of each of the documents.

As already explained in the previous paragraph, the most frequent terms are influenced by the chosen list of stop-words.

Here are our results:

1. Plain text

Still little can be deducted from this view. Let's see if the other versions may give back something more informative.

2. Divided by sections

From this version we can, in fact, start extracting some interesting knowledge:

- the second section is the longest yet less dense part of the book;

- the first, on the other hand, is the shortest yet most dense and readable.

Good reasoning may be that the first section is the one in which many characters, places, and situations are introduced, therefore it results to be denser in terms of vocabulary, and overall more readable. Or, we may assume that the other sections present more dialogues or original forms (such as misspellings or lines in other languages - French, Italian or German), therefore they appear less readable than the first.

Another interesting point can be found in the last section “the most characteristic terms”: we could, for example, deduce which characters or topics may be more prominant than others and have a prior overview of each section.

Let's see if we can go a little deeper with the version divided by chapters.

3. Divided by chapters

Moving to this last version, the one divided by chapters, we are definitely getting more detailed information.

The Second Section:

- While be the overall longest, it is not the one with the longest chapter within, being them Chapter 3 from the Third Section (“Revolving Doors”) and Chapter 2 from the First (“Metropolis”);

- It seems to have three among the five shortest chapters of the whole book (Chapter 6 “Five Statutory Questions”, 7 “Rollercoaster”, and 8 “One More River to Jordan”);

- Apparently features four out of the five less readable chapters of all (while, we have deducted from the previous version the third section being the overall last in this category). This may also be because the Second Section has more chapters than the Third so the other ones balance the general evaluation. Wihtout knowking this fact, we couldn't have assumed something like this.

The First Section:

- Confirms to be the one with the longest, most dense and readable chapters.

Let’s know investigate the “most characteristic words” section: as previously foreshadowed, each chapter presents in the list its most prominant characters/protagonists and topics.

5. Trends

"Trends shows a line graph depicting the distribution of a word’s occurrence across a corpus or document."

This tool lets the user visualise the frequencies of a specific set of terms across documents in a corpus or segments (by default 10) of a document. The initial set is a small group of the five most recurring terms, but it can be modified as pleased. The visualisation features a little legend, colours, and also options to change the type of graph the user wants the trends to be shown in.

Jimmy

As already stated, Manhattan Transfer has so many characters that it is impossible, and also incorrect, to pick a proper protagonist. Nonetheless, some of them are more relevant and frequent in the whole narration then others. Among them, one, in particular, stands out: Jimmy Herf.

With its 240 appearences “jimmy” is one of the most recurring terms of the book, however this is not the only way the character is referred to. Some have a nickname for him, some others misspell his surname, at one point we discover his birth name, etc. Let’s see how many are they and how they change in the course of the narration.

Plain text:

By sections:

By chapters:

Ellen

Far more interesting are the trends of the second most present character, Ellen Thatcher. She gets married - and changes surname - multiple times, has several nicknames, etc. Let’s see how her character changes through the narration.

Plain text:

By sections:

By chapters:

Less notable characters

The same type of analysis can be conducted also on less notable characters, those who may die at some point or just appear in a couple of chapters. Let's see, for example, the poor Bud Korpenning. Without prior knowledge, it is clear that after Chapter 5 ("Steamroller") he is no longer there or at least not mentioned: in fact, he commits suicide by jumping off Brooklyn Bridge by the end of said Chapter.

Plain text:

By sections:

By chapters:

Or, let's pick a less tragic one: Congo Jake. In this case, what's really interesting to note is that this character is addressed as "Congo Jake" fewer times than "Armand Duval", who is he? Still Congo. In fact, Congo Jake is a French sailor who became a good friend of Jimmy Herf during World War I. He emigrates to the US after the war and becomes a bootlegger. Suddenly wealthy, he takes the name "Armand Duval" and lives on Park Avenue where he hobnobs with other millionaires. Without prior knowledge, we wouldn't have been able to make the comparison between the two names.

Plain text:

By sections:

By chapters:

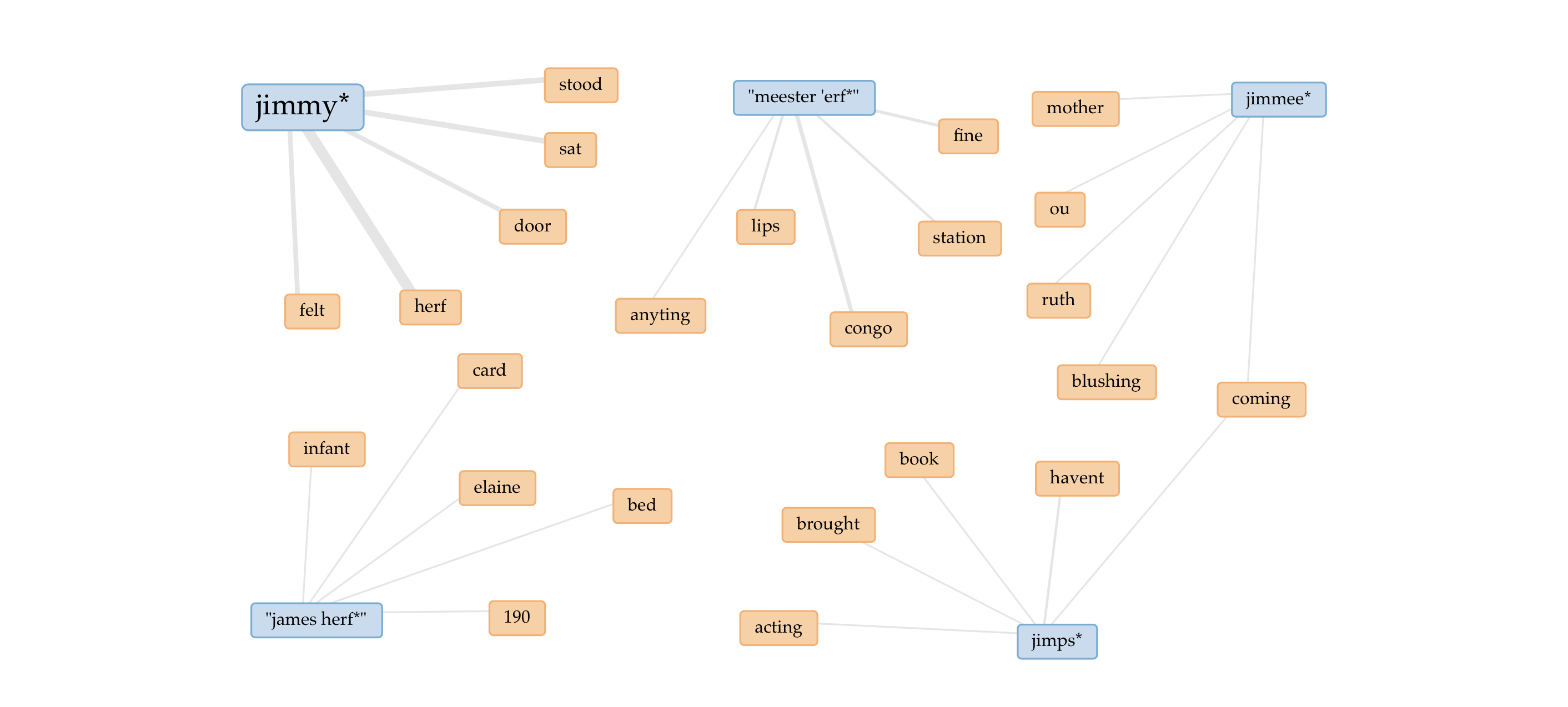

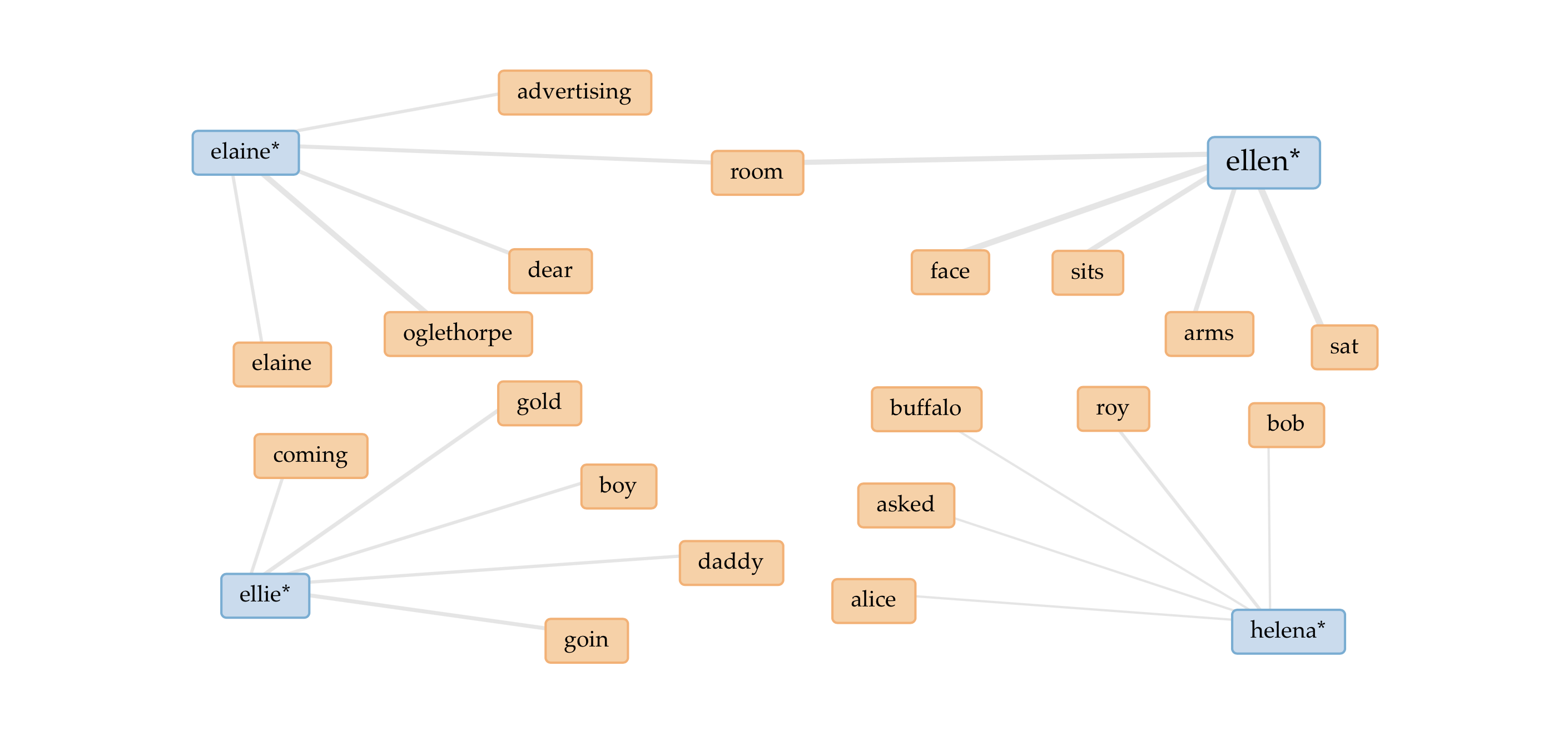

6. Links

Sticking to Jimmy and Ellen, let's see what Links - a tool which highlights all connections between high-frequency words through a dynamic network graph - can tell us.

Jimmy

Ellen

Now, in both cases, what Links can tell us - or at least foreshadow - is how some of their names are "linked" to other terms. For example, "meester 'erf" is strongly linked to "congo" because the character named Congo Jake usually misspells Jimmy's name into that. Or "herf" is strongly linked to "jimmy" since he is typically addressed as Jimmy Herf, his full name. Moving on, "elaine" is strongly linked to "oglethorpe" assuming that this is the way she is usually called in the span of chapters in which she is still married to John. And so on and so forth.

7. Conclusion

Voyant is undoubtedly a straightforward and intuitive tool for distant reading.

In our case, given the number of characters in this work, we decided to pick Voyant’s options which could give us back some interesting information about them taken singularly or in comparison. However, little can be done without proper tagging, which is not supported by Voyant.

Many of our characters have several ways to be addressed, some very different from their standard name (see, for example, the case of Congo Jake). It is an understanding then that the user needs prior deep knowledge of the text before the actual analysis, otherwise he/she/they can just play around and see what comes out.

Voyant remains a great starting point for computational text analysis given its variety of tools and the many different visualization options it provides.